|

| Curtis Harold Stamey |

My dad died today, at 1:30 PM on May 31, 2024. I want to do

something to memorialize him, to leave a piece of him for the future to find.

To yell into the cavern of time so that his name can echo for just a bit

longer.

If I were a musician, I would write him a song so that I

could sing it when I felt alone, so I could lift my voice and light up the

darkness with memories of my father. But I am not a musician. If I were a

painter, I would paint a picture that would capture his heart and soul and make

his bigness and loudness and love obvious to anyone who sees it. I am not an

artist.

I write. I want my words to sing to you. I want to use them to paint you

a picture. So I’m going to try. I want to introduce you to my dad.

[Let’s start with some light violin. A note here. A note there. Nothing too fancy. Something

sweet and light and drifting. A pencil sketching on a canvas.]

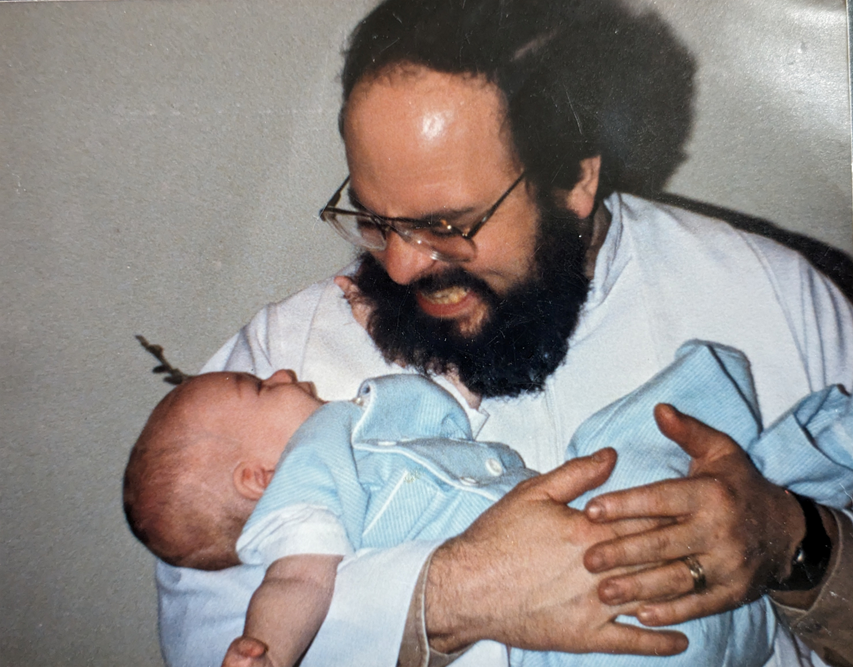

I choose to remember Curtis Harold Stamey as a short man with a big presence. He was about 5’6” tall, bald, and he had a magnificent bushy black beard. When I was a small child, he would bounce me on his large belly and playfully scratch my face with that beard of his.

|

| Author's note: That baby is not me. I was much cuter. |

He met my mom in church, at a Sunday school class for

college students that he taught even though he was a college student too. They

fell in love and were engaged within six weeks. If my kids read this someday, I

want to point out that whirlwind romances usually do not last. This one did.

Quote from my mom: “Sometimes, impulsive decisions work

out.”

[Our violin music starts to find its form. Another string

enters the song, something with some bass. It mirrors and enhances the violin. There

is a structure in this song after all. The pencil marks on the canvas are

starting to look like something, but we don’t know what yet.]

Newly married Curtis wanted to be a professor. He moved to

Tuscan to go to graduate school. They bought land. That was going to be home. Then

a new, charismatic preacher moved into Curtis’s church. My dad found the Holy

Spirit. This was not wonderful news for my mom. She was happy enough to go to

church, but she was not all-in on this Jesus thing.

Quote from my mom: “He found the Holy Spirit and was too

happy. It was annoying.”

The fellowship that my dad was hoping to get to pay for his

doctorate went to someone else. Meanwhile, my dad’s infectious love of Christ

eventually wore my mom down, and she too fell in love with that first century

carpenter who was also the Son of God.

Quote from my mom: “I married a professor-to-be. I didn’t

want to marry a pastor. But he loved Jesus so much, and he felt called. So we

went.”

Years ago, he told me about that decision. He did not want

to go. He had a life set out for him. But God wouldn’t stop calling. God

wouldn’t leave him alone. On the night he decided, he walked his land. Felt the

rocky sand beneath his shoes. Listened to the wind. He mourned the life he was

letting go of while embracing the life that God put in front of him.

[The song is full now. We have our strings and brass and

drums. It’s a strong song, happy and purposeful. The pencil sketch is complete.

It’s my dad, his arms wide in anticipation of a hug. His face is lit by a

smile. The artist starts painting the canvas, bringing depth and light to the

picture.]

Author’s note: I’m going to abandon the idea of a linear

story here. I’m going to present you with disconnected vignettes. My dad would

like that. He loved people and stories, but he didn’t have a place for linear

thought in his head.

-

I remember building models with him. Little cars and tanks

and planes. We would go the model store and pick out our next project, buy

dozens of little square paint bottles that made satisfying clicking noises when

you lined them up on the table, and buy tiny little brushes to paint all the

fiddly details.

I would glue my fingers to the model. I would get glue-y

fingerprints on the canopies of the planes. I would line up my paint brush just

so, and then slop the paint all over the model.

“Do you want some help with that?” I could hear the smile in

the voice. I didn’t look at him.

“No. I can do this,” I said with boyish confidence.

He used to make model ships with intricate rigging. He hated

the rigging. He swore at it, struggled with it, sweated, and turned red trying

to get it to get it just so.

“Why do you do those?” I asked.

“It relaxes me,” he said between gritted teeth. I did not

understand.

-

Dad used to teach Kenpo Karate. I loved the gis. They were

thick canvas and they had patches and big bright belts. My dad was a teddy bear

most of the time but was an actual bear when he was sparing.

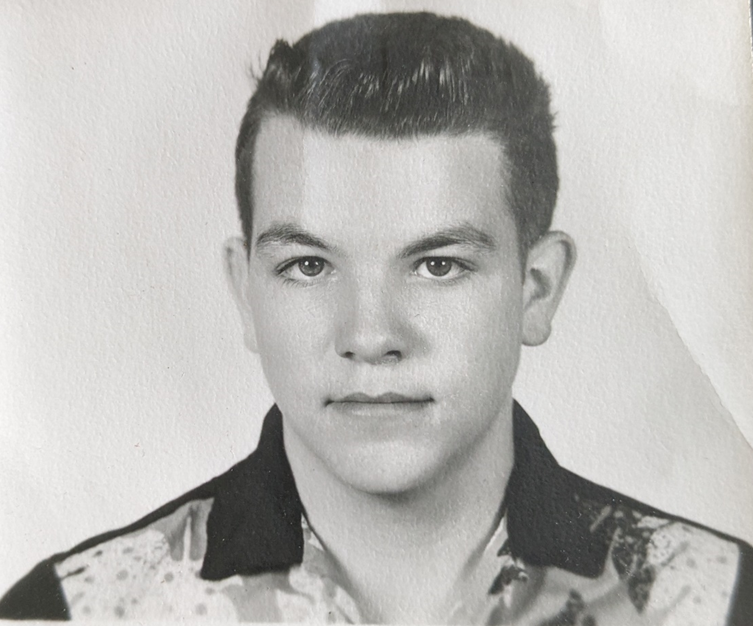

Lee, my older brother, was good at fighting. He was tall and lanky and strong and fast. I don’t remember him losing to the other kids. Once, in a tournament, he round-house kicked a kid out of the ring. I thought that was the coolest thing ever.

I was not a good fighter. In that same tournament, I did so

poorly that the other kids were volunteering to fight me. In the next match, I

back-handed the kid in the ear. This was not a legal move and cost me points,

but seemed necessary. So I did it several more times. I lost the match.

|

| I'm the one on the right who looks like he's going to trip on his own shoes. |

Lee sparred my dad once. He came in with a big round-house

kick, the kid-ejecting kind of kick. My dad’s hands made a sort of blurring

motion, and then Lee went flying backward. That night my mom told me he used to

spar without pads because they didn’t have them back then. He would come back

home black and blue.

My mom: “You do this for fun?”

My dad: “I think so.”

-

My dad is on the pulpit. He is wearing his white robe. His

rainbow stole is catching the Easter morning sunlight. His hands are outspread,

palms open as if he is going to hug the entire congregation. This is my dad at

the peak of his preaching powers. His voice booms like friendly thunder.

He is sharing his love with his people, and he is perfectly

at home.

He holds up a loaf of bread and tears it in half.

“This is my body, broken for you.”

He holds up an old clay chalice.

“This is my blood, shed for the forgiveness of sin.”

I, and the rest of the congregation, are transfixed by this

bearded, be-robed man who loved Jesus so very deeply.

-

We were eating dinner in Bonners Ferry when a man knocked on

the door. My dad opened the door and started talking. The man was homeless and

jobless and looking for a new start. His skin was pale, his face scruffy, and

his eyes drawn and tired. He and my dad left shortly after. Junior high me

sighed. Another dinner ruined by work.

I met the man a few months later while running errands with

my dad. He was healthy and happy and grateful. His eyes were bright. Maybe it

was okay that dinner was interrupted after all.

[The song begins its turn. The major notes shift to minors. Grays

and blacks and bruising purples and blues are added to our painting. There are

storm clouds behind my dad and shadows line his face.]

My grandpa Harold died when my dad was fifteen. My grandma

re-married. Grandpa Ed was a rigid man who believed in hard work and structure.

Grandpa Ed and my dad would fight often, and Grandpa Ed would die without my dad

reconciling with him. This would define my dad’s relationship with authority

his entire life.

-

My dad was given ailing churches that he would turn around before

being sent to another church. This process was good and necessary and painful.

People don’t like change, even people who know change is necessary.

During his last assignment at Bonners Ferry, he bought a mug

that said, “Life’s a bitch and then you die.” As a junior higher, I did not

understand the difficulties of his job or the stresses involved in trying to

save a church that doesn’t want to be saved. But I knew that a pastor who owns

a mug like that is a pastor in crisis.

I did not know what to do about it, so I didn’t do anything.

-

After twenty years of service to the church, my dad was

forced into early retirement. I do not know why. At this point, I don’t believe

I ever will.

-

I was sitting on the steps of a church after a retreat, feeling the warmth of the

evening sun on my face. The light was golden, and the shadows were long. My dad

was inside, talking too much and too long. It was his last retreat before

his retirement.

One of my dad’s friends sat down next you me.

“There are a lot of people in heaven because of your dad.

He’s a great man. I’m going to miss him.”

-

My dad, a man with two master’s degrees, worked minimum wage

jobs to support his family. He stocked dishes at Dansk. He did not get along

with his boss. He tried to stage a mini-coup by arranging the new dish display.

It did not end well.

-

My dad eventually took a teaching job at Daybreak, a

substance abuse center for teens.

My dad: “I don’t think we’re giving these kids enough

credit. I think, with the right education, all these kids can succeed.”

High school me, thinking about some of my classmates, “Some

people are dumb, Dad. I think you should lower your expectations.”

My dad: “We’ll see.”

After a year, I asked my dad how it was going.

“Tom, some people are just dumb. But we love them anyway.”

[The song becomes dissonant. The instruments clash, screech,

and wail. Great splashes of paint are spread over the painting, obscuring my

dad and his smile.]

Dementia is cruel. My dad’s last decade on earth is a story

of slow isolation. He would become angry for no discernable reason. Family

meals would end with yelling before he stormed off. We didn’t know yet that it

was because his mind was breaking.

-

Dad would call. He would be upset but wouldn’t be able to

process why. He would talk in circles. I would listen.

“I know dad. Yeah. I don’t know.”

Silence.

“I love you, Dad.”

Click.

-

I walked into my house after the extended absence caused by

COVID. My dad was in his wheelchair. His beard was gone. He didn’t look up.

Adult me: “Hi, Dad. It’s me. It’s your son. Tom.”

Dad: “Oh. That’s nice.”

-

I sat in a chair next to my dad’s bed.

My mom handed me her Bible. “Do you want to read to him?”

I read him some Psalms. He did not respond. He couldn’t. I

listened to the oxygen pump. Listened to his strained breathing. I read some

more.

[The discord stops. A single violin plays a last, sweet

note. The paintbrush is laid down, my father’s smile and hands just visible

through the mess.]

Dementia does not provide its victim with much dignity at

the end. My dad could not say goodbye. He could not say he loved his four

children. He could not make wrong things right. So we did it for him. His kids

gathered together this week (Lee was there in spirit). We told stories. We

laughed. We sat is silence. We cried. I cried so very much.

My dad was a complicated man. He struggled with authority

and the pain from his forced retirement, and that struggle became all the more

difficult as the dementia set in. But, in another sense, he was a very simple

man. He loved Jesus and he loved people. He did both those things with abandon.

I will miss you dad.

|

Comments